To him she was a fragmented commodity whose feelings and choices were rarely considered: her head and her heart were separated from her back and her hands and divided from her womb and vagina. Her back and muscle were hired into field labour…her hands were demanded to nurse and nurture the white man… Her vagina, used for his sexual pleasure, was the gateway to the womb, which was his place of capital investment – the capital investment being the sex-act and the resulting child the accumulated surplus…

Barbara Omolade, “Hearts of Darkness”, 1983

In the book “Caliban and the Witch: Women, The Body, and Primitive Accumulation”, first published in 2004, researcher Silvia Federici quotes the above excerpt in her reflections on the history of witch-hunts. These become an introduction to the analysis of the woman’s status in the capitalist system, her position in family structures and socially-assigned roles. In her research, Federici connects the expropriation, as it were, of women with the necessity of reproduction assigned to them. This dependency allows the capitalist economy to exploit unpaid labour, which in these relations was usually left to women. Federici shows the institutionalization of rape and prostitution or the witch-hunt trials as methods of subjugating women and appropriating the effects of their labour.

The expropriated labour of women and their sexuality are exploited by the capitalist world, its economy, and state institutions. According to Federici, in speaking of women’s labour, we often mean household work, unidentified with the professional realm and therefore subject to subtle manipulation and symbolic violence that the contemporary world still tolerates. This unpaid household work has become an attribute of femininity. The housewife’s hell continues to be presented as a synonym of paradise, bliss, and the love act that the man offers to “his woman”. In a joint exhibition, Paulina Ołowska, Agata Słowak and Natalia Załuska address these stereotypes as ways of thinking about women’s labour, the female body, and female sexuality.

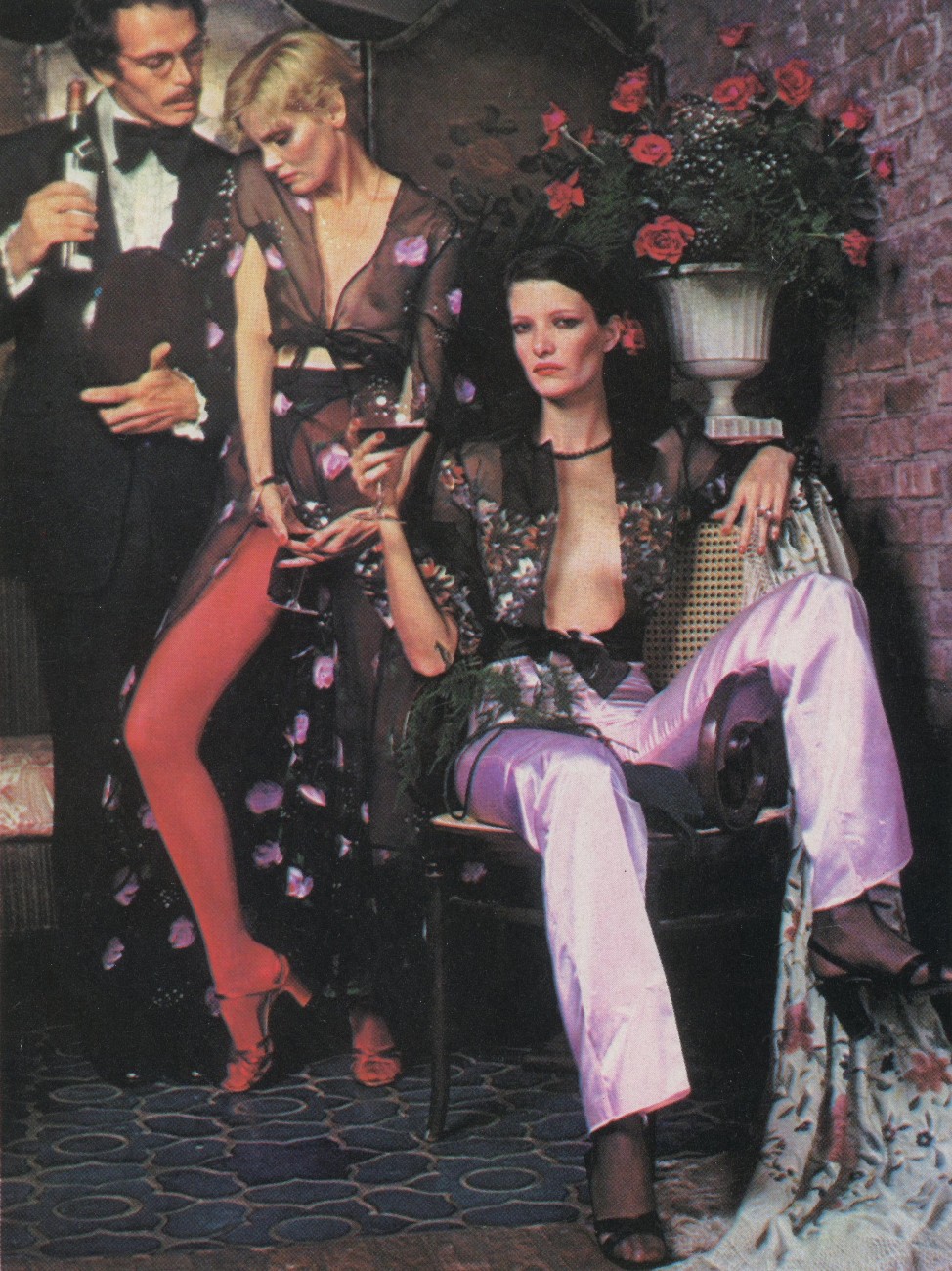

Experimenting with formalistic painting tissue, comprrised of brushstrokes, texture and the patch, Natalia Załuska imbues it with secret and sensual elements. There is a constant exchange between the two areas: modern form and female sensibility. The emotions hidden in her paintings become heated, while elsewhere they hide themselves, building a single harmoniously functioning shape. A dialectic of geometry and corporeality, modernism and sensuality, becomes for Załuska a means of expressing her own sensibility. Agata Słowak, in turn, creates a vocabulary of her own symbols that she uses to describe reality. In her narratives, inspired by traumatic, brutal female experiences, she develops several themes. Słowak constructs a story about women weary with the daily struggle for corporeal empowerment, the artificial system of social norms, symbolized here by clichés from classic art history, the fragile condition of which is upset by bold eroticism that disrupts existing norms or conventions. Paulina Ołowska in her paintings works through the relation between the eroticism of the picture and the economics of the art world. A woman’s and artist’s relationship with this reality becomes for her tantamount to the perversions of the capitalist economy, which in a bulimic impulse keeps devouring and spewing forth ever new images and meanings. Ołowska’s paintings lure temptingly, but they also bring attention to the dark side of artistic work, which is no longer a modernist act of genius creation, but a gesture of exhibitionism, of exposing one’s secrets and desires.

The show’s title, borrowed from a 1975 book by Silvia Federici, alludes slyly to feminist postulates, raised for many years, demanding wages for household work. But the artists – Paulina Ołowska, Agata Słowak and Natalia Załuska – refer in their work to much broader issues: not only the systemic exploitation of women’s unpaid labour, but also the contemporary world’s attitude to female sexuality. It turns out that women’s empowerment, their autonomy, agency, and independence, remain far from given. That is why the idea of “wages for housework” is crucial for a reflection on the visibility of women’s art as well as its place in the contemporary economy.

Marta Kudelska